News snapshots

January 2013-June 2013

10 January 2013: What is in a word? For decades studies how the words we use reflect the perceived complexity of the world around us. Franz Boas the famous anthropologist studied the culture and language of the Inuit people as they adapted to their world of ice snow, reindeer. It is not surprising that he found that these people have a huge compliment of different words to describe different types of ice, snow, and the sky above. I would suppose that noticing subtle differences in the environment that we have trouble seeing then results in generating the need for word labels that capture what is seen. Our word labels also results in determining how we see and interpret our world. That world could be as varied as snow and ice the sounds of cello, or the quality of wood used to make furniture.

12 January 2013: We can train (improve) all kinds of executive functions and that is the case not only in kids throughout the development but also in well functioning adults. Researchers such as Ellen Langer and others has shown that you subjects can be trained to be more mindful, and can be trained to meditate and improve their ability to concentrate and the positive effects could be substantiated using brain imaging techniques (with improved conductivity between dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and brain regions involved in attention and working memory. The point is rather simple an obvious. We can learn cognitive skills and not just facts.

13 January, 2013: Is it really a surprise? In the Jan 8 2013 issue of Cell Metabolism Parks and colleagues report their findings that the body’s response to high-fat and high-sugar diets has a large genetic component. So here is more evidence that obesity (including Body Mass Index) is not just determined by what you eat but also your genetic heritage.

17 January 2013: Deer mice build complex burrows (their homes). The evolutionary/molecular biologist Hoekstra and colleagues have been able to identify the DNA fragments that account for variations in tunnel architecture in these little mice. Findings like these certainly should influence how we see the mix of nature and nurture in shaping complex types of behavior.

1 February 2013: Yet another non-surprise but nevertheless an important finding and point of view. Nora Volkow (Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse) and colleagues published an article on the neurbiological basis forfood addcition and obesity (see The Addictive Dimensionality of Obesity,” Biological Psychiatry, February 2013). There is lots of speculation in this report and some data but the bottom line seems to be that “drug and food addiction allegedly share genetic, molecular, neurobiological, and behavioral mechanisms that, when coupled with environmental triggers, have “the potential to facilitate or exacerbate the establishment of uncontrolled behaviors. “

4 February 2013: There are many examples of fiction designed to explore scientific ideas, findings, methods. In some instances exploring mind/brain science is at the heart of fiction (novels, stories). Maria Konnikova is a doctoral candidate in psychology at Columbia University, and is working on a novel Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes. She is working with the well-known psychologist Walter Mischel whose work is described on this website. To learn more about her work search for the January 2013 issue of Scienceline.

8 February 2013: The science is remarkable, dramatic, finding a way to store huge amounts of data in DNA. Ewan Birney and colleagues have done just that and describe how they did the deed in a January 23, 2013 issue of Nature. They also document the history of work that led up to their own contribution to this novel method for storing information

15 February 2013:The long tradition continues unabated of studying all sorts of animals to better understand ourselves. Birdsong has long been of interest to scientist interested in the neurobiological foundations of language. It turns out that about 80 genes active in the brains of humans and songbirds such as zebra finches and parakeets. These genes are important for imitating sounds, speaking and singing. Birds that can’t learn songs or mimic sounds don’t have those genes in their brains. This is also a nice esthetically pleasing example of systematic disciplined science providing clear and important findings. For more details search for the summary of the work of Erich Jarvis and colleagues, presented at February 15 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

18 February 2013: Fighting obesity doesn’t get easier. It turns out that children with fat fathers show epigenetic changes that make them vulnerable to becoming obese. The finding is not all that surprising given what is known about the link between parental condition and the epigenetics and health (paper in Nature, 2010). Adelheid Soubry, started with what is known, that it takes 2 months for sperm to mature providing an important window of paternal influence, and then found that children with obese fathers were likely to have less methylation, or hypomethylation, on a certain region of the IGF2 gene than children whose fathers were not obese. This is one factor that can increase the liklihood of becoming obese (see Soubry et al., “Paternal obesity is associated with IGF2 hypomethylation in newborns: results from a Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) cohort,” BMC Medicine, 1741-7015-11-29, 2013.

20 February 2013: One of the mechanisms that may account for age-related impairments in forming new memories may be through changes in NMDA receptor subtypes. It is well known that the NMDA receptor is a major player in forming memories but also in sculpting or cleaning out memories that are no longer necessary (a bit like cleaning a hard drive of junk files). For more information see the article by Tsien in the January issue of Scientific Reports.

26 February 2013: The FOXP2 and associated proteins have been shown to be important for the production of speech. Bowers and colleagues, in a study published in the Feb 2013 issue of The Journal of Neuroscience have shown that the amount of FOXP2 protein in the brains of female rat pups is greater than that in males (and related to amount of pup vocalization). In addition similar differences in the amount of this protein was also seen in children’s brains (bases on a small sample of children who had died in accidents).

27 February 2013: Studying the biological basis of complex behavior in humans is really tough so scientist turn to simpler beasts. Cornelia Bargmann studies the neural circuitry of complex behavior like eating, socialization, and sexual behavior and because they have simple nervous systems comes up with a mechanistic picture of what drives their behavior. This is a casebook example of science research (picking the right questions, the appropriate subjects (worms rather than people) and applying sophisticated and powerful neuroscience tools. Beautiful work and for the detail see, Nature 494, 296–299 (21 February 2013).

18 March 2013: Perhaps the best way to blunt drug abuse relapse is to prevent the stress that is often the trigger once again using drugs. In the real world that may be hard to accomplish and certaintly not as reliably accomplished than in laboratory animal studies. Kauer and colleagues have shown that when you block kappa opioid receptors (which are activated by stress which then activates the ventral tegmental area of the brain. They also showed that stress interrupts long term potentiation (which is accounts for strengthening connections of between neurons which then also hinders the ability to inhibit dopamine release by blocking the neurochemical GABA (and it should be noted that dopamine is a key player in pleasure response and addiction). See Graziane et.al. in the journal Neuron (77, 942-954; March 6, 2013)

19 March 2013: A new treatment combining two hormones can reduce appetite (a combined therapy using the hormones glucagon and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and may form the basis for a new treatment for obesity and diabetes in the future. GLP-1 stimulates the release of insulin to lower blood sugar and also acts at the brain to reduce appetite.

Stephen Bloom and colleagues reported their results at the Society for Endocrinology annual conference in the UK.

21 March 2013: Salk scientists discover how the brain keeps track of similar but distinct memories. Fred Gage and his colleagues discovered how the dentate gyrus, a subregion of the hippocampus, helps keep memories of similar events and environments separate, a finding they reported March 20 in eLife. Recalling a memory-such as the location of missing keys-does not always involve reactivation of the same neurons that were active during encoding. More importantly, the results indicate that the dentate gyrus performs pattern separation by using distinct populations of cells to represent similar but non-identical memories.

23 March 2013: Starlings may have bird brains but they are not that different form the brains of mammals. It is therefore interesting that sleep plays an important role in the brain’s ability to consolidate learning (even when the it involves the memory of competing tasks). See full report by Brawn and colleagues in an article in the March issue of Psychological Science (entitled, Sleep Consolidation of Interfering Auditory Memories in Starlings). The though is that sleep is protective and strengthens memory.

27 March 2013: Especially when you are old it is unhealthy to be alone because that can lead to illness and an early death. Social isolation (not so much the feeling of lonliness) is correlated with higher mortality — even after adjusting for pre-existing health conditions and socioeconomic factors. See Steptoe, A., Shankar, et. al in the J. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. March (2013).

3 April 2013: There is something wrong with this picture. The front page of the NY Times of 31 March 31, 2013 points out that about 20 % of high school age boys in the United States have received a medical diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). So every fidgidy little boy that bothers a teacher enough to send for help is vulnerable for the diagnosis of ADHD and consequently to be put on a drug to combat it. This is crazy state of affairs and highlights the absurdity of the current psychiatric diagnostic practice.

10 April 2013: You can study stress and it consequences in so many surprising places, in all kinds of subjects, and in the context of a wide range of conditions. Turns out that stressed female squirrels improve the survival odds of their pups through the action of maternal hormones. The details of the study are reported by Dantzer and colleagues in Online Science and the title of their article is Density Triggers Maternal Hormones That Increase Adaptive Offspring Growth in a Wild Mammal

17 April 2013: For decades we have been dissuaded from studying incredibly complex cognitive functions such as the nature of consciousness. During the last several decades that scenario has changed through the use of new tools such as brain imaging and other techniques. Now anesthesiologist have gotten into the act by uncovering distinctive brain activity patterns in “vegetative” patients under anesthesia. Patrick Purdon and colleagues looked at brain activity in epileptic patients as they received increasing doses of the commonly used anesthesia drug propofol in preparation for surgery. You can learn more about the patterns of brain activity associated with consciousness in their paper in the November issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and in a related article by Pearce and colleagues published in the January issue of the journal Brain.

19 April 2013: Again we are reminded that our cognitive prowess is not as special as we think and some birds are capable of cognitive feats that we thought were reserved for humans. There is a wealth of findings demonstrating some of the cognitive skills of birds such as those of the jay and crow family (such as being able to make and use tools. We now have evidence that some birds such as parrots can trade an immediate nut reward for a better reward later (just like in the Mischel marshmallow study with very young kids who at 4 had trouble trading an immediate reward for a much better one later. Should we call this planning, or strategic inhibition….not sure but the results of birdbrain activity are certainly surprising. Read more about it in an article by Alice Auersperg and colleagues in the March issue of the journal Biology Letters.

27 April 2013: So much of what is of value is in the packaging. And so it is for what makes our brains such effective learning and adaptive tools. During fetal development in some species the cerebral cortex undergoes huge changes, increases, in surface area folding tissue along with niumbers of neurons. The driving force behind this process is the nuclear protein called Trnp1 which is the key regulator of this crucial process. For more details of the mechanisms behind this process see the article by Götz and her colleagues in the April 2013 issue of Cell (Pages 535-549).

4 May 2013: Here is a study on stress and relapse and functions that are related to resilience that is very noteworthy. It involves a study in 45 recovering alcoholics in which brain scans are used to predict which patients are likely to relapse. The data used to make the predictions were brain-imaging scans that captured regional brain activity while the patients were relaxed as well as when they were imagining stressful experiences. Those patients with elevated activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) EIGHT times more likely to relapse in 3 months than those patients who did not increased activity in this brain region. Thee patients also exhibited elevated brain regions associated with craving, reward and pleasure (even while they were supposedly relaxed. This subgroup of patients with elevated vmPFC activity may have said they were relaxed but there brains ‘said’ otherwise. It should also be noted that the vmPFC is a brain region that plays a key role in all sorts of executive functions which includes resilience. It is therefore not surprising that many alcoholic patients self-medicate by using alcohol as the ‘drug of choice’. For more details read the article entitled “Brain Scans Can Predict Which Alcoholics Are Most Likely to Relapse” by Rajita Sinha and colleagues in the May issue of JAMA Psychiatry.

This pic is all too familiar….just like the eating addiction findings

6 May 2013: The new and not necessarily improved 5th. Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is about to be published. Too bad. Droves of scientists would agree with Tom Insel (Director of NIMH) that the revised DSM classification system for mental disorders is fatally flawed. How are you ever going to make progress in understand the nature of mental disorders if you can even identify them accurately? How is it possible that the DSM was once again designed around casually held belief systems rather than being based on the wealth of decades of what we have learned from neuroscience and genetics about how minds work? I guess if you know what is the right answer then why do you need evidence to back it up.

7 May 2013: How often do we have to be told what we know? Does repeating it over and over make our knowledge more reliable? Once again we are told that food addictions is associated with compulsive overeating and of course also involves the dopamine reward system (which plays a major role in drug addiction and the experience of all sorts of rewards). Stop! I believe it.

11 May 2013: Current neuroscience research continues to tickle and excite. The study cited below is just one more demonstration of brain plasticity and its consequences. Genetically identical mice roam about and explore to differing extents but those that are more ‘cognitively’ active grow far more neurons than the more inactive mice. Here is another example of how variations in behavioral interaction with the environment result in differences in brain plasticity. One of the authors of the paper, Gerd Kempermann, concludes, “To out knowledge, it’s the first example of a direct link between individual behavior and individual brain plasticity,”…see the details of the study in 9 May issue of Science (J. Freund et al., “Emergence of individuality in genetically identical mice,” Science, 340:756-59, 2013).

11 May 2013: What is the trajectory for how preadolescent children learn scientific reasoning (including skills for evaluating evidence and formulating hypothesis and experiments to test them? Piekny and Maehler built a study around the concepts proposed a decade ago by Klahr and Dunbar and found that the development of the components of scientific reasoning in young children proceeds unevenly. “The development of …. scientific reasoning begins with the ability to handle unambiguous data, progresses to the interpretation of ambiguous data, and leads to a flexible adaptation of hypotheses according to the sufficiency of evidence. When children understand the relation between the level of ambiguity of evidence and the level of confidence in hypotheses, the ability to differentiate conclusive from inconclusive experiments accompanies this development.” For more details see Br J Dev Psychol. 2013 Jun;31(Pt 2):153-79

October 2012-December 2012

4 October 2012: It is now possible to grow new neurons by reprogramming pericytes (a brain cell) with just the use of 2 proteins. The complete findings are reported by M. Karow et al., “Reprogramming of Pericyte-Derived Cells of the Adult Human Brain into Induced Neuronal Cells,” in Cell Stem Cell, 11: 471-76, 2012

6 October 2012: Is addiction to a drug (or anything else) a brain disease? That question of and similar ones that focus on behavioral problems keep getting asked despite all of the cumulative and growing number of findings about brain changes in addiction. Does the question really matter? Who cares whether an addiction is or is not a disease? What does matter is trying to understand the basis foundations of addictions, how they develop and what can help treat them. Nevertheless it is worth reading Dirk Hanson’s website article on addiction in his September 26, 2012 edition of the ‘Addiction Inbox’. He starts by quoting Charles Dickens and then travels through a maze of conjecture and science. His article can be found at http://addiction-dirkh.blogspot.com/2012/09/does-brain-research-obscure-addictions.html.

11 October 2012: I don’t understand how science proceeds. Are of the histories of what has been learned from past research totally ignored? What is the shelf life of scientific knowledge? Can past scientific findings go stale and therefore have to be discarded? It turns out that the anesthetic ketamine has been found to rapidly lift depression (over a period of days). Ron Duman at Yale reports the findings in Science along with his National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) research colleagues. Twenty-five years ago I, along with NIMH studied the effects of ketamine on cognition. What we noted it is that ketamine induces psychotic like symptoms that are quite unpleasant. We saw nothing that resembled a drug that had anti –depressant effects. At that time other investigators observed many of the same effects of the drug. I guess times have changed.

17 October 2012: The parade of attempts to treat the cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s Disease continues with a new twist. Tradtionally treatments used either are designed to slow cell death or inhibiton of cholinesterase, an enzyme believed to break down a key neurotransmitter involved in learning and memory. Using a rat model of Alzheirmer’s disease. Harding and Wright have a) demonstrated that the peptide angiotensin IV is capable of reversing learning deficits seen in many models of dementia and b) the drug Dihexa is even more powerful than the brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, a growth-promoting protein associated with normal brain development and learning (see the October 2012 iaaue of Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics for more details).

30 October 2012: Some mind/brain science sounds like science fiction but isn’t. Neuroscientists Hampson and colleagues have published a paper in the September 2012 issue of The Journal of Neural Engineering describing how an implanted devise could substantially improve thinking (decision-making and problem solving) in 5 monkeys that had previously brain functions impaired with large doses of cocaine. It is just one of many similar studies that may set the stage for similar manipulations (effects) in humans.

3 November 2012: In Walter Mischel’s famous marshmallow experiment we learned that 3-5 year olds when told that if they could wait a few minutes they would get lots more goodies instead of the two they could get and eat immediately. Most kids can’t wait. It turns out however that the results can be quite different if the children are in a lab situation where they can trust the reliability of the person running g the experiment (as opposed to someone they had experienced being unreliable). Not a surprise at all and of course the results have all sorts of practical implications (see Kidd et. al. in the October issue of the online journal Cognition).

10 November 2012: Chance events, nature, have a way of unexpectedly impairing scientific progress. In June of 2012 a freezer malfunction at McLean Hospital in Boston destroyed a collection of brains from autism patients. It took years to collect these brains, which were the basis of more than 100 published studies on autism. Early this November Hurricane Sandy was responsible for having all of the freezers fail at New York University School of Medicine and that massive thaw destroyed precious research findings from a whole host of studies.

20 November 2012: The placebo effect continues to interest mind/brain scientists. While the most recent findings are not surprising they do highlight what we have known for some time. In one study researchers documented what types of people are more (or less) likely to get pain relief from a placebo. The study is based not only on personality measures but also brain imaging data. For example it turns out that that people ‘who scored high on resiliency, altruism, and straightforwardness, and low on measures of “angry hostility”—were more likely to experience a placebo-induced painkilling response’ (see M. Pecina et al., “Personality Trait Predictors of Placebo Analgesia and Neurobiological Correlates, in Neuropsychopharmacology, 2012). In another placebo study rats also obtain pain relief from placebos just like humans. This is really not a surprise since their placebo response is based on simple conditioning (which is likely to also account for the human placebo response). That study was published in journal PAIN in October 2012 and was based on collaboration between Neubert and Niall Murphy, and the two of them decided to look at placebo responses because that deals with pathways and mechanisms that relate to pain, reward and addiction.

15 Dec 2012: On the PBS News Hour (2 days ago) we hear the much-repeated story by Nora Volkow and other that multiple (rather than single) genes are likely contenders for predisposing individuals to substance abuse. It is highly likely that this is the case for most behavioral disorders and also underscores that we are still muddling along when it comes to refining our psychiatric classification system.

18 December 2012: Insulin is a critical player in glucose metabolism and therefore it is not surprising that it is also important in brain metabolism. As such it is critical for neuron growth, neuroplasticity, and neuromodulation. It is now being considered as important in the pathogenesis of both neuropsychiatric and metabolic disorders is inflammation. No doubt we will hear lots more about the role of insulin, and thereby brain metabolism and brain inflammation in determining all sorts of brain disorders.

19 December 2012:The bottom line has been clear for some time. Neglected babies are grossly cognitively impaired and one of the reasons is that they develop less myelin (white matter) which insulates brain neurons which is needed to allow these neurons to function normally. Charles Nelson and his colleague team of researchers have published more than 50 papers demonstrating the impact of early social isolation which has powerful destructive effects on the brain and cognition. While this has been known for a long time the details and extent of the damage becomes ever clearer. In one recent study based on work with rat pups (published in mid September 2012 in Science by Ralph Adolphs and colleagues) the huge cognitive deficits observed in developmentally isolated pups is accounted for at a molecular level of analysis. In another study Gabriel Corfas and colleagues found that brain white matter development is markedly impaired in infants raised in socially isolated environments (Online issue of Science, mid September 2012). These types of studies have huge implications for our understanding of normal vs. pathological human development.

20 December, 2012: The Flynn effect (IQ keeps going up over the last many decades) has been studied and interpreted for some time (see Flynn, J. R. (1987). Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin, 101,171-191) for just one of many articles on this topic. Flynn’s work (including his analysis of a great deal of IQ data collected from many over many years) rekindles the smoldering debate about what is meant by intelligence, different forms of intelligence and the impact of the environment on intelligence (in making us smarter in a rich environment and less intelligent in an impoverished environment. These are old issues that have never lost their luster

July 2012-September 2012

July 6-11, 2012: What is an opiod receptor made of? It is ironic. Trying to deal with a food addiction or other life style problems that impact our health (significantly) is low-tech science that is built on virtually no cumulative knowledge. In contrast we are privy to stories like the one that appeared in Nature in which Ray Stevens and his collaborators (at Scripps) and, separately, Brian Kobilka at Stanford have provided a detailed pictures of the atomic structure of the opiod receptor. Imagine getting down to the very chemistry of a brain neuron. Now that is the kind of science you can build on and perhaps apply it to problems like drug addiction. Also in the last few weeks I, and the rest of you, have read still reports about how a cancer victims genetic map can be used to identify what make their gene map different from those of other folks and this provides a strong clue as to what may have gone astray resulting in their particular brand of cancer. Having that information can be useful in determining exactly what kind of treatment may help that patient. Obviously this is quick script is highly oversimplified. For example the patient’s cancer may be more of an issue of a gene being ‘inappropriately’ turned on (or not tuned off) rather than the mere presence of a gene mutation. Nevertheless this is another example of science getting to the heart of the matter of what ails us.

July 22, 2012: I think another remarkable part of this story is that the basic findings appeared in Nature a couple of months ago and ten days ago NIH sponsored a conference that focused on exploiting (translating and applying) these findings. Wow!!!!

July 28, 2012: I read the article while being stunned and breathless. The bottom line implication of the study is that a history of stress (depression to be more precise) may be a risk factor that increases the likelihood that breast cancer cells will end up metastasizing to bone and lung.mWe are talking about the neurobiology of depression and not simple depressed women having been treated for breast cancer not taking care of themelves as well as women without a history of depression. Oh shit Liz, (my wife who died of breast cancer at 48) you got hit by a triple blow and a perfect storm. I guess it would suggest that women with breast cancer and a history of depression should be treated vigorously with anti depressants (which unfortunately are far less effective than the pharma ads would let on). The study used mice as subjects but an epideomological study in women would not be hardto do. (See J. Campbell et al., “Stimulation of host bone marrow stromal cells by sympathetic nerves promotes breast cancer bone metastasis in mice,” PLoS Biology, 10: e1001363, 2012.

July 29, 2012: Above I described the extraordinary science achievement of uncovering the chemistry of what makes up an opiod receptor. Here is another story just like it (in terms of the power of biological reductionism highlighting how our brains work). The science story is that it is possible to define how many proteins are required for a neuron to release its neurotransmitters. The vesicle binding to a cell membrane in the brain takes place in a few hundred microseconds and the proteins that are released are the stars of neural transmission. So the investigators of this study are at their at the origins of the action of neural transmission. I would think that this finding would be exploited in the very near future. (See L. Shi et al., “SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open,” Science, 335:1355-59, 2012.

July 29, 2012: What does it take to convince policy makers that we know enough to apply what we know? When is science evidence ripe enough to get translated into social policy? “The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) underscore the importance of an enriched environment during infancy and childhood and may help explain the increased rates of depression and anxiety disorders known to exist among institutionalized children.” Jon Bardin reports this in the July 24, 2012 issue of the Los Angeles Times. The report in the Proceedings of the NAS also points out that brain-imaging studies substantiate the impaired brain development of socially deprived infants. In the 1930’s Renee Spitz showed that physically well taken care of orphans who have little interaction with adults are developmentally severely damaged and even the interactions of young adults that are also a bit lacking in smarts and maturity can make a huge difference in the development of these children. How large must a font be to get the attention of individuals that can improve the development of disadvantaged infants?

22 August 2012: It is not surprising that not all monkeys are alike. They can think differently from one another, use different strategies to achieve the same goal and these differences are reflected in differences in neural activity. Daniel Moran and his doctoral student, Thomas Pearce published their results in the July 19, 2012 issue of Science. Sometimes it is nice to confirm what you assume you already know while also uncovering more of the details of what has always made sense, i.e., individual differences in cognition are common in humans, monkeys and all sort of other animals and those differences can be defined by the neural mechanisms that are the basis of those differences.

26 August 2012: The impact of sleep on memory and learning is an area of research that keeps on giving but with little opportunities for closure. For example there is an extensive literature on the role of sleep in consoldating existing memories. In this most recent sleep and memory/learning study Anat Arzi and colleagues have demonstrated that even while asleep people can still learn brand new information such as new associations between smells and sounds (and the complete findings are reported in the online edition of Nature Neuroscience (August 26). What does that tell us about the activity of the sleeping brain?

14 September 2012: We have known that infants that experience early isolation demonstrate a whole host of social and intellectual development problems. It has also been demonstrated that these effects are the result of isolation induced effedts on brain grey matter (brain’s neural cells). This is not surprising since the strength and connections between neurons are determined by learning and experience. Gabriel Corfas, and colleagues have now demonstrated that the damage caused by isolation in early development also damages the brain’s white matter, glial cells, which produce the fat and protein myelin sheaths that insulate a neuron’s branching axons (from a study reported in Science September 14.

19 September 2012: By implanting a brain stimulator in two neighboring layers of the cerebral cortex, layers, called L-2/3 and L-5 , Theodore Berger, Robert Hampson, and collegues demonstrated that they could improve thinking (decision processes) in monkeys. One of the coauthors pointed out that the device used in the study could be contained in an implantable chip. We have seen and will continue to see studies with these kinds of findings.

October 2011

1 October 2011: Endocannabinoids may play an important role in eating addictions. In addition the neuropetide orexin (also called hypocretin) which plays a role in cocaine addiction but also is important in eating compulsion. Dr. R.A. Espansa and colleagues at Wake Forest University showed that orexin increases a rat’s drive for more sugar even though they are well-fed but not when they are hungry. The findings are published in the European Journal of Neuroscience 31(2) 336-348, 2010. The evidence is scanty and it is a huge leap from rodents to people,…..these sorts of findings invite thoughts of a magic pill that can be used to treat over eating disorders.

2 October 2011: Some findings make us stop in our tracks. It seems that age-related chemical signals in blood impair new neuronal growth while young blood can stimulate neuronal growth in old brains. Researchers studied pairs of old and young mice that were joined at the hip (using a technique called parabiosis), which causes them to develop a shared circulatory system. Tony Wyss-Coray, and colleagues reported their result in the August 31,2011 issue of Nature.

5 October 2011: When neuroscientist harness sophisticated technologies amazing findings can emerge. Laura Sanders in the September 28, 2011 issue of ScineceNews describes how brain-imaging methods can capture what a person in watching. The study was conducted by Jack Gallant and two of his colleagues at UC Berkeley who also served as the subjects in the study. Using the imaging machine a computer program produced a movie that recreated what they were looking at. You would agree, Wow.

10 October 2011: Are you happy and if not why not? For decades neuroscientists have studied the genetics and neurochemistry of mood and mood disorders. The neurotransmitter is known to be involved in mood regulation and the gene that encodes the serotonin-transporter protein, appears to play a role in happiness. In a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, published in 2009, Joan Chiao and Katherine Blizinsky of Northwestern University, in Illinois, found a positive correlation between the gene and mood disorders. This finding has also been used to explain differences in different racial and national groups and perhaps will help explain why the elder and young are happier than the middle aged.

11 October 2011: Don’t confuse me with evidence I know what I know and what I know is correct. While the popular notion is that educational policy should be evidence-based too often belief systems based on biased thinking and personal communications with oneself are the basis of what is done in schools. Diane Halpern and her co-authors point this out in Science 23 Sept. 2011; 1706-1707). They show that there really is no scientific support for the notion that there are advantages to single-sex schooling. In fact, on the contrary such schooling may exaggerate gender stereotyping.

12 October 2011: Hearing Bilingual: How Babies Sort Out Language an article in the today’s New York Times by Perri Klass describes several science treads relating to the acquisition of language in babies. A variety of cognitive neuroscience methods have proved useful in demonstrating that: monolingual infants at 6 months can discriminate between phoneti8c sounds; by 12 months these same babies no longer detected sounds in a second language (neural commitment); in contrast bilingual babies did not detect differences in phonetic sounds at 6 months but by 10-12 months could discriminate sounds in both languages. It may be the case that bilingual children benefit broadly beyond their double vocabulary. They may be cognitively more flexible and better equipped to use different strategies for solving problems.

14 October, 2011: What were we like 100,000 years ago? Our brains have barely changed but our knowledge has exploded. It does however appear that our ancestors of from that far away time were cognitively facile. They may have had far less knowledge but they could accomplish some sophisticated thinking. The New York Times (14 October 2011) included an article summarizing an article that originally appeared in entitled “In African Cave, Ancient Paint Factory Pushes Human Symbolic Thought Far Back”. A discovery from the middle stone age (100,000 years ago) provides evidence that the Homo Sapiens that lived at that time knew how to make pigments, used them for decoration and pushed way back the date of higher order cognition (symbolic thinking). The full report (submitted by Christopher Henshilwood) of the findings appear in the October 14, 2011 issue of Science.

15 October 2011: We are often told that a and b are related but are then left wondering why. What is the basis of a significant correlation between a and b? It turns out that low birth rate is associated with a five fold increase in the incidence of autism. The full findings are based on an epidemiological study by Jennifer Pinto-Martin, director of the Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities Research and Epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania in the October issue of Pediatrics. So what is it about low birth rate that seems to be associated with autism? What is the reason why normal birth weight babies can also develop autism? Is the incidence of autism in low birth rate babies similar to all kinds of other impairments. I guess an association like this one is a bit of a scientific tease.

25 October 2011: Ahmad Salehi and colleagues report in today’s online Translational Psychiatry that genetic variant that makes small tweaks in an important brain protein (BDNF) may cause aging related exaggerated declines in cognition in some people more than others (in their study they used pilots as subject). About 38 percent of pilots in carried the variant in either one or both of their copies of the BDNF gene. flight simulator scores of all the pilots in the study declined a little with age but scores of pilots carrying the variant dropped about three times faster than scores of pilots who have the normal version of the gene.

28 October 2011: We can learn from Woodpeckers how to avoid head injudry. Ming Zhang and colleagues reported in Plus One structures that protect them from brain damage given the fact that when they peck away the deceleration force is 1000 times the force of gravity. Incredible. What they have learned about the proctective head gear of the woodpecker can be applied to equipment like better football helmets.

July-September 2011

12 July 2011: What are the prospects of a memory implant that might rehabilitate impaired memory. Of course that is not possible now but maybe… One intriguing step in that direction was reported in the Journal of Neural Engineering by Theodore Berger and colleagues. Rats were implanted with electrodes, and threaded down into the hippocampus, a structure that is crucial for forming new memories. The device transmits exchanges between CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus to a computer, which mimics the firing patterns associated with learning, and remembering and so affected memory in the rats.

22 July 2011: Increasing the strtructure and promoting active (rather than passive learning is helpful to all of us. What Haak and colleagues demonstrated in an introductory biology class is that daily practice in problem solving, data analysis and other higher cognitive skills disproportionately helps capable but poorly prepared students. (Science; 2011; Vol. 332, 1213-1215)

23 July 2011: Hold on and this will catch your breath and make you eyes water. To be effective math teachers should know math. Schmidt, et. al. (in Science; 10 June 2011 1266-7) looked at the relationship between measures of math ability and knowledge based on the well established TIMSS study (Trends in International Mathematics and Science) It turns out that US 8th graders are about in the middle compared to math achievement of similar kids in many other countries. This is not a surprise. We have been there many times before. Equally unsurprising is the strong linear relationship between math and achievement and math teacher knowledge. Knowing about math cognition can help in teaching math but it is not a substitute for well-prepared knowledgeable teachers. Amazing.

1 August, 2011: The National Research Council, in its July 2011 report, proposed a new framework for improving American science education by focusing on core ideas and teaching students how to think about and approach problems rather than memorizing facts or covering lots of topics superficially. Why is it taking so long to adopt what obviously makes sense? We have known this approach to science is what differentiates countries with strong science education curriculum and those that are not successful in teaching science (TIMSS studies)

16 August, 2011: When does the accumulation of evidence finally put a scientific problem to rest? What does it take for us to say, with a high level of certainty; we know our findings are correct? Laura Beil in the August 27th, 2011 issue of Science News; Vol.180 #5(p. 22) reviews the link between food dyes and childhood hyperactivity. There isn’t any and this has been shown over an over. A leader in this field of research, Bernard Weiss, University of Rochester School of Medicine, along with a panel of experts certified color additives in food and hyperactivity in children in the general population has not been established.

16 August, 2011: Of course we know that child development means brain development and this is reflected in how kids think, solve problems and learn. In a fascinating brain imaging study of 2nd and 3rd grade children calculated easy (3 + 1 = 4) or more complex (8 + 5 = 13) addition problems while have their brains scanned using functional MRI. The researchers, Vinod Menon and colleagues, reported in the July issue of NeuroImage that 3rd graders behave differently from 2nd graders in their approach they approach to the arithmetic problems. Second graders solved easy and hard problems in the same way while 3rdgraders approached the difficult problems using a different strategies because the easy solution strategies had been somewhat automated. The brain imaging data of the older children showed heightened activity in brain regions important for working memory (a function that is involved in keeping recently acquired information readily available.

18 August 2011: Maybe the scientists that published a widely heralded paper on the power of social networks spoke too soon and too loud. Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler got lots of attention when they put forth data that suggested that obesity can spread like a virus through social network. Gina Kalota in the August 8, 2011 issue of the New York Times cites just a few of the statistical gurus that have reviewed and challenged the data and papers on the power of social networks pointing out that the authors conclusion don’t hold up and don’t make much sense. Just because a finding strikes our fancy doesn’t mean that it is valid.

1 Sept. 2011: Here we go again. Over the last 30 years there have been many studies published that have examined the relationship of food dyes and childhood hyperactivity. For example in 1976 in the journal Pediatrics, published a study “that compared a regular diet with a diet that eliminated artificial flavors and colors in (only) 15 hyperactive children. After eating what has since become known as “Feingold diet,” children showed an improvement in symptoms such as difficulty paying attention.” The problem is that there are many studies that have demonstrated no effect of food dyes on hyperactivity. Unhappily the problem lands right in the laps of the FDA.

6 September 2011: It turns out that exercise can improve neural functioning by enhancing oligodendrocyte cells which have a major role in insulating myelin around neurons’ message-sending axons. Neurons transmit messages more efficiently (faster) when they are mylenated. Fields and Wake reported the results in the online journal Science on Aug. 4, 2011. Any manipulations that can increase nerve cell mylenation is important not from the standpoint of basic science but also its practical application

May-June 2011

27 May 2011: Recent research has provided us with new insights for understanding and treating dyscalculia. The research by Butterworth and colleagues reported in the May 27 2011 issue of Science (1049-53) once again illustrates the importance of understanding the neural basis of a cognitive function (such as numerosity) for appreciating the malfunction of a cognitive function.

27 May 2011: Here is one more voice from a prominent economist, Hernando de Soto, telling us why the financial debacle of 2008 happened. He concludes that that it was a “staggering lack of knowledge” (see article in Bloomberg Business week May2-May 8, 2011). He argues that knowledge was not accessible in; what was inside of bundled mortgages, risk ratings of bonds and banks, accounting summaries that did not capture the health of institutions. Would it not be more appropriate to describe actions taken during the financial crisis as being based on false knowledge rather than lack of knowledge? This is an important issue in how science proceeds. Ignorance is far less lethal than strongly held beliefs without much factual foundations, and faulty evidence that happens to fit our biases. Clinical psychiatry is a good example of false knowledge run amuck.

27 May 2011: Amarnath Thombre, vice president of strategy for match.com working with a small staff of mathematicians and statisticians uses findings based on what clients of the site do (their choices of contacts, rather than information gleaned from the questions they answer such as their preferred characteristics of the kind of mate that they are looking for(see article in Bloomberg Business week May2-May 8, 2011). Once again we see evidence that what we report about ourselves, our values, beliefs, is often a poor predictor of behavior. The business world is well aware of that.

30 May 2011: Teaching college physics using the scientific knowledge we have accrued about the development of expertise produces far better results than through the use of standard methods of teaching introductory physics. This topic of the development of expertise has been reviewed on this site in several postings. Effective use of expertise training in teaching physics focuses on well designed practice and teaching strategies “in the form of a series of challenging questions and tasks that require the students to practice physicist like reasoning and problem solving during class time while provided with frequent feedback.” The study results are presented in Science, 13 MAY 2011 VOL 332 by Louis Deslauriers and collaborators.

Another example of using principles of expertise training was described in the New York Times, Science Times Section (June 7) by Benedict Carey. The title of the article is Brain Calisthenics for Abstract Ideas. High school students are taught to image the graphic representation of mathematical equations and expressions. This training pro0vedes them with better, deeper, understanding of the meaning of math concepts and simulates how mathematicians think about mathematical functions. Students should be able to image the function of an equation and if not their understanding of that function is likely to be rather shallow.

5 June 2011: The design of cognitive interventions (in both normal controls and subjects with some impairment) needs to be evidence based. In an article in Science (2011 May 27; 332(6033):1049-53) Butterworth and colleagues identified neural markers of dyscalculia using structural and functional neuroimaging studies. The data obtained provides some of the neural correlates of deficits in understanding sets and their numerosities which is necessary in elementary school mathematics.

21 June 2011: Nicholas Wade, in an article that appeared in The Science Times (N.Y. Times, 21 June 2011), provides an elegant, beautiful picture of how basic neuroscience can provide important information about mind-brain relationships. In the article we are treated to the science of understanding the neural network of roundworm behavior. The worm is transparent and only one millimeter long. Over thirty years ago it was the favorite experimental animal of Sydney Brenner and others that learned from his scientific experience. Now Cornelia Bargmannis decoding how the brain of the round worm functions (all 302 neurons and 8000 synapses of the little beast.

28 June 2011: What can you learn from single case studies of the gifted or impaired subject? How valuable are reports of highly unusual behavior reported in the popular press rather than in scientific journals. I am not sure of the answer but nevertheless am intrigued by unusual phenomena like that of a 12 year old autistic child who develops his own theory of relativity, taught himself calculus and is considered a PhD prospect at Indiana University (as reported in the Daily Mail Reporter 24th March 2011). It took me a while to post this snapshot because I was and remain uncertain of its scientific value.

January-April 2011

11 January 2011: Many books have been written about how science can be used as an instrument of evil. Here is yet another one that rings an especially powerful cord throughout the New Bretten community. Sheila Weiss has just published a book ‘The Nazi Symbiosis: Human Genetics and Politics in the Third Reich’ Univ. of Chicago press, 2010. As the title suggests she documents how genetics research was usurped by the Nazis to support racial policies and ultimately the death of millions.

11 January 2011: Oxytocin, a hormone released from the brain’s hypothalamus, has again been reported to promote feelings of trust. Carsten DeDreu (University of Amsterdam) and his colleagues report their findings in the January 11, 2011 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is the same hormone that induces rat mothers to nurse their pups. What is up in the air is the question of how big is the oxytocin effect in humans? Is it comparable to being stroked or complimented or given a nice warm piece of apple pie?

29 January 2011: Neuroscience exposes pernicious effects of poverty is the title of an article based on the work of the Neuroscientist Helen Neville of the University of Oregon published in Science News (January 29th, 2011; Vol.179 #3 , p. 32). The title says it all. Children growing up in poverty, have much poorer brain development and cognitive development. They show deficits in executive function and self-control language skills IQ, attention and working memory. The good news is that these functions are trainable and programs that target these cognitive skills have met with some success. Some of these programs appear as postings on this website.

15 February 2011: The title of the article by Karpicke* and Blunt summarizes their study findings in the online publication Science. They found that’Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping’. This is yet one more recent study that provides strong evidence that testing (retrieval) during the course of learning is more valuable than the same amount of study time. The theme of the importance of retrieval testing in learning is reviewed in the posting on this website entitled “What clothes would the naked emperor have worn had he known he was naked?”

20 February 2011: It is not a big effect but the mechanism behind what may be happening makes the finding that ‘Aerobic exercise boosts memory’ intriguing. Coauthor Arthur Kramer of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign coauthored the study report in the February issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The experimental group walked fast enough to get heart rate up 3 times a week for 40 minutes while a control group devoted an equal amount of time to body toning exercises. The walkers demonstrated a modest improvement on standardized memory tests but perhaps more important demonstrated an increase in the size of the anterior hippocampus a brain site involved in memory and one of the few places where new nerve cells are born from adult stem cells throughout a person’s life.

11 March 2011: In the March 2011 issue of Scientific American there is an article reporting on a symposium entitled Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) education, part of the most recent annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Mark Stefanski, a high school biology teacher and other panelists spoke as one voice. Students should learn to understand the process of doing science (including scientific inquiry). They point out that too much of science is taught as linear process with an emphasis on context absent facts. It turns out that the longer students study science the more they dislike it. Something is terribly wrong with this picture.

11 March 2011: At the same AAAS meeting David Smith, (State University of New York at Buffalo) and Michael Beran, (Georgia State University) presented the findings from a study in which monkeys trained to play computer games (using a joy stick) appear to express self-doubt and uncertainty rather like humans by not making a choice rather than risking making the wrong choice. We are not the only creatures that are self-aware.

11 March 2011: Bob Herbert wrote an editorial on the Op-Ed page of the 5 march 2011 issue of the New York Times entitled ‘College the Easy Way’. He points out that colleges and universities have lost their mission of providing a comprehensive and meaningful education to students who, by the way, pay lots of money for their education. Training is no longer rigorous; students expect not to have to study, think, work at learning, hone skills like critical disciplined thinking. Students (and their families) are short changed and society suffers especially in an economy in which brain power is the ingredient that allows us to compete in a global economy. Fixing this dismal picture of academia will be difficult. Students won’t go to schools that demand that they act like students and may opt for the campus that provides fun and games majors.

4 April 2011 : David Brooks wrote an interesting op-ed article in today’s New York Times entitled Tools for Thinking. He starts the article by mentioning a question raised by the well known cognitive scientist Steven Pinker. “What scientific concept would improve everybody’s cognitive toolkit?” He goes on to describe some of the contributions to respond that question at an Edge.com sponsored symposium that included 164 big league thinkers. Some of the contributions included: 1) the Einstellung (Set) effect whereby we try to solve new problems that worked in the past; 2) Focusing Illusion (fixated on the importance of what you are thinking about in the here and now); 3) Fundamental Attribution Error (ignoring alternative explanations). What is most interesting about the symposium is the question itself that was being addressed and the implications of what we come up with not just now but later when we have had a chance to really digest what we know about cognition that can really make a difference in how we think. This deserves more discussion.

12 April 2011: Reading minds in the 21st. century. That is the theme of Benedict Carey’s article in the Science Times section of yesterday’s N.Y. Times. In it he describes attempts at unearthing the psychology, the minds of political leaders, especially the ‘bad guys’ such as Libya’s Qaddafi. There is a long historical tradition of trying to figure out what your adversary leader is thinking and while the tools for doing so has multiplied the scientific basis for the appraisals remains soft and of limited value. The raw data that is used by pundits of psychological profilers such as Jerold Post (George Washington University), Margaret Hermann (Syracuse U.), David Winter (Michigan U.) and Peter Suedfeld (U. British Columbia) include analytic clinical case-case approaches, content analysis of writings (i.e., number of times” I, me, mine…” are used) and dynamics such as level of certainty in a leader, aggressiveness, coherence. I would not want to bet my life on the output of these analysis but at the same time I would guess that they are better than chance in predicting a leader’s behavior.

15 April 2011: A couple weeks ago an article stating that cell phones increases brain activity in a brain area nearest to the phones antenna. One of the authors of the study published in the March issue of theJournal of the American Medical Association is Nora Volkow who also happens to be the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse with lots of experience as a researcher using brain imaging techniques. The study did not conclude anything about lasting negative effects from using cell phones. I wonder what other conditions produces increases in brain activity. Would sitting close to a computer or near a TV or going through a metal detector at airport security also trigger changes in brain activity? What really is the size of the effect in comparison to all kinds of other conditions in our lives?

22 April 2011: In a recent newspaper interview published in the UK (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news) we read about the extraordinary talents of a 12 year old boy with Aspergers syndrome (a mild form of autism). The boy taught himself calculus, algebra, geometry and trigonometry in a week is developing his own theory of the origins of the universe, and is working on an expanded version of Einstein’s theory of relativity. While the Mozarts of this world rarely happen the fact that they do occur and we marvel at what such a mind can come up we might also ask what can we learn from such unusual people about the development (and genetics) of mind/brain relationships.

September-December 2010

1 September 2010: The mechanisms that are responsible for brain plasticity, learning, is considered to be the number one problem in the study of how our minds work. The recent work of the Harvard neuroscientist Michael Greenberg illustrates how far we have come at identifying the fundamentals of how experience affects brain growth and development. His work and that of other neuroscientists has identified, at a molecular level, the underlying mechanisms of brain plasticity including how genes are turned on as a result of experience. So when we think of leaving a record of experience in memory we are not only c0nsidering the chemistry of how neurons communicate with one another but also the genetic events that activated within a cell. More about this work will be detailed in a story based on a dialogue with the gifted geneticist Joni Rutter.

27 September 2010: Harvard Professor March Hauser has been found “guilty of eight infractions involving three published papers and other unpublished work”. Now what do you do? His work has been found to be highly influential in how we think bout the characteristics of the human mind and he seemed to prove that the features of nonhuman cognition share much in common with the working of our brains. Do we repeat his flawed experiments? Do we make believe his findings don’t exist? How do we erase from our minds false knowledge? False knowledge especially when it is incorporated into how we think about important issues is far worse than ignorance.

27 September 2010: When grasshoppers are stressed it speeds up metabolism and so they consume loads of sugars and carbs. When they are relaxed they choose foods rich in proteins. It all makes sense in that when we have to make a run for it we need fuel now (athletes also ‘know’ that and so they load up on carbs before and during a marathon). Read more about the findings by Hawlena and Schmitz in the Proceedings of the Sciences September 21, 2010, 107 (38) and summarized in Nature News. Perhaps the obese that are heavy consumers of carbs are using as their fuel for dealing with chronic stress (just a thought).

3 October 2010: A feature article by Winnie Hu entitled ‘Making math as easy as 1, pause, 2, pause describes the value of importing The National Math System of Singapore into the suburban New York City elementary schools. That system for teaching math to kids has been hugely successful in Singapore for at least 2 decades. It is designed to provide elementary school children with a deeper understanding of the meaning of numbers by slowing down the learning process to give kids a chance to think and reflect. Without that kind of understanding kids will continue to struggle throughout the school experience leaving them math impaired. Read more about learning about numbers in the posted story “What do large and small numbers mean to me?”

7 October 2010: The most read article (written by Robbins) on the Guardian (UK) website last week was one that spoofed science journalism. Writing about science is often dull, written as if by formula, not much fun. Why shouldn’t learning about science be interesting and fun and therefore much more effective.

12 October 2010: Some basic mind-brain science research findings have obvious practical implications. Yet one more example is illustrated by research that demonstrates that parts of the brain that normally are specialized for hearing can be recruited for visual information processing. The study led by Stephen Lomber, (based on findings obtained from deaf cats who were the study subjects) appeared in the October 12, 2010 issue of Nature Neuroscience. Laura Sanders summarized the study in the October 10, 2010 issue of Science News. What other areas of the brain can support more than one function? Perhaps there is something to the observation that deaf people often have great vision. The full reference to the study is: S. Lomber, M. A. Meredith and A. Kral. Cross-modal plasticity in specific auditory cortices underlies visual compensations in the deaf. Nature Neuroscience (Published online October 10, 2010).

14 October 2010: Stress speeds up the metabolism of grasshoppers and so they consume sugars and carbohydrates that are more digestible. When more relaxed they prefer foods high in proteins which they need to grow and reproduce. The research that appears in the journal articles listed below have implications for the grasshopper ecosystems but may also be relevant to food consumning habits in humans (such as preferring to reach for a sugary snack when stressed) and perhaps may also account for the eating habits of the obese among us.

Hawlena, D. & Schmitz, O. J. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15503-15507 (2010).

Hawlena, D. & Schmitz, O. J. Am. Nat. advance online publication doi:10.1086/656495 (2010).

Kauffman, M. J., Brodie, J. F. & Jules, E. S. Ecology 91, 2742-2755 (2010).

26 October 2010: In late August we posted a news snapshot about fraud in science. We wrote the following:

When candor and honesty in science is missing the consequences can be disastrous. This last week two stories appeared in the news one dealing with outright misrepresentation of mind-brain findings and the other dealing with a corporate late stage clinical trial of an Alzheimer’s disease drug that went ‘sour”. March Hauser a prominent and gifted neuroscientist (evolutionary cognitive neuroscience) at Harvard had to retract published papers in highly visible journal because of the disconnect between observations and his reported conclusions. He may be asked to resign his professorship. His career is seriously damaged and the public’s view of the world of scientific research is undermined. We can speculate about why he would ‘fudge’ what he reported in papers but it is certainly a shame that his contributions will be lost to science and that the public will once again wonder about the nature of science and the credibility of what science has to offer. The other story is what must have been a lack of internal company candor at the pharmaceutical company Elli Lilly. The company stopped a clinical trial of a drug that was tested because it had anti (Alzheimer’s) dementia properties. It turns out that the drug did not improve the symptoms of dementia but made them worse (compared to placebo treated subjects). How could the scientists at Lilly not have suspected that a positive response is unlikely given all the pretesting that was done before such a late stage clinical trial was launched? I suppose in discussions leading up to launching the clinical trial staff did not want to be the bearers of bad news. As a result 100s of millions of dollars were lost and a promising drug did not live up to what it was promised to be.

The news story may have been premature, wrong.

Weeks later and having a second look at the story tells us things are not necessarily as simple as they appear. The Science section of the New York Times, the 26 October 2010 edition, printed an article by their science reporter Nicholas Wade which makes what appeared to be clear rather opaque. His close colleagues have reported in an open public letter that he has unimpeachable integrity. Hauser’s attackers have been known to be over-the-top critics of his research. The principle accuser outside of Harvard, Gerry Altmann, the editor of the journal Cognition, now says he may have been wrong. Others have pointed out that ‘miscues in the lab’ and not fraud may have taken place.

The issues of perceived fraud, witch hunts, pressure to publish and push careers, get grant support, academic/research combat is well worth exploring in a separate subsequent, posting.

On second thought things are not necessarily as simple as they appear. The Science section of the New York Times, the 26 October 2010 edition, printed an article by their science reporter Nicholas Wade which makes what appeared to be clear rather opaque. His close colleagues have reported in an open public letter that he has unimpeacheble intergrity. Hauser’s attackers have been know be over-the-top critics of his research. The principle accuser outsife of Harvard, Gerry Aoltmann, the editor of the journal Cognition, now says he may have been wrong. Others have pointed out that ‘miscues in the lab’ and not fraud may have taken place.

26 October, 2010: Genetic determinants appear to be players in many forms of psychiatric disorders. Two very recent reports provide us with additional details in our picture of the causes and perhaps treatment of mental disorders. In the current issue of Journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research Kirk Wilhelmsen and colleagues report that up to 20% of the population caries a gene that makes them especially sensitive to alcohol. Thgis gene is responsible for the enzyme CYP2E1, which is involved in metabolizing ethanol alcohol.

In another study Michael Kaplitt and colleagues published a study in the October 20 issue of Science Translational Medicine demonstrated that depressed individuals have lower than normal levels of a protein called p11 in the brain’s nucleus accumbens (a brain structure also involved in reward and drug addiction). The investigators delivered the gene for the p11 protein to the nucleus accumbens and eliminated depression-like behavior in listless mice.

1 November 2010: Violent prisoners have difficulty in using information about potential risk and gain in decision making. The details of these results (including the mathematical models used to calculate prisoners’ reaction to value of rewards and losses) can be found in an article by Thorsten Pachur, Yaniv Hanoch and Michaela Gummerum, in the in the October 2010 issue of Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. Complex decision making research under conditions of reward and loss is now a well developed area of study based on sophisticated behavioral tools and associated brain imaging methods and measures.

9 November 2010: When you learn how to get and stay fat as a teenager that skill stays with you as into your adult years. Gordon-Larsen and UNC colleagues found that obese teenagers become severely obese by the time they are 30 years old. Not a surprise but what do you do with the data. One obvious implication work exta hard at developing healthy life style programs for teenagers. Read more about the study in JAMA. 2010;304(18):2042-2047.

10 Nov 2010: In an earlier post on Einstein’s brain we reviewed the role of glia cells in accounting for his super smarts and imagination. The role of glia continues to be of great interest to neuroscientist everywhere especially whether these cells are capable of neuronal transmission. The issue is reviewed in a recent article entitled “ Settling the great glia debate: Do the billions of non-neuronal cells in the brain send messages of their own?” By Kerri Smith (the journal Nature 11 November 2010 468, 160-162 (2010

15 November, 2010: There are many types of expertise that are poorly defined because they can’t be defined in terms of explicit knowledge and operations. As a result this type of expertise can’t be taught as easily in settings like the classroom. “No, management is not a profession” is a feature article by Richard Barker in The Harvard Business Review (August 2010). The subtitle of the article is ‘Some business skills can’t be taught in a classroom. They have to be learned through experience. This means that the skills required of a successful manager are not (or barely) explicit. It also means that the knowledge of a manager is ‘soft ‘and that management expertise cannot be the foundation of a useful model. I wonder to what extent this state of affairs also holds for the state of the art of economic decision making. Obviously management, including economic planning, invariably involve highly complex decision making where implicit expertise (rather than explicit elements)are the basis of how experts decide what to do. The point often is made that the idiosyncratic nature of our behavior makes data or rule driven decision making problematic.

16 November 2010: Violent prisoners have difficulty in using information about potential risk and gain in decision making. The details of these results (including the mathematical models used to calculate prisoners’ reaction to value of rewards and losses) can be found in an article by Thorsten Pachur, Yaniv Hanoch and Michaela Gummerum, in the in the October 2010 issue of Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. Complex decision making research under conditions of reward and loss is now a well developed area of study based on sophisticated behavioral tools and associated brain imaging methods and measures.

19 November 2010: When you learn how to get and stay fat as a teenager that skill stays with you as into your adult years. Gordon-Larsen and UNC colleagues found that obese teenagers become severely obese by the time they are 30 years old. Not a surprise but what do you do with the data. One obvious implication work exta hard at developing healthy life style programs for teenagers. Read more about the study in JAMA. 2010;304(18):2042-2047.

19 Nov 2010: In an earlier post on Einstein’s brain we reviewed the role of glia cells in accounting for his super smarts and imagination. The role of glia continues to be of great interest to neuroscientist everywhere especially whether these cells are capable of neuronal transmission. The issue is reviewed in a recent article entitled “ Settling the great glia debate: Do the billions of non-neuronal cells in the brain send messages of their own?” By Kerri Smith (the journal Nature 11 November 2010 468, 160-162 (2010

20 November, 2010: There are many types of expertise that are poorly defined because they can’t be defined in terms of explicit knowledge and operations. As a result this type of expertise can’t be taught as easily in settings like the classroom. “No, management is not a profession” is a feature article by Richard Barker in The Harvard Business Review (August 2010). The subtitle of the article is ‘Some business skills can’t be taught in a classroom. They have to be learned through experience. This means that the skills required of a successful manager are not (or barely) explicit. It also means that the knowledge of a manager is ‘soft ‘and that management expertise cannot be the foundation of a useful model. I wonder to what extent this state of affairs also holds for the state of the art of economic decision making. Obviously management, including economic planning, invariably involve highly complex decision making where implicit expertise (rather than explicit elements)are the basis of how experts decide what to do. The point often is made that the idiosyncratic nature of our behavior makes data or rule driven decision making problematic.

14 Dec. 2010: Translating basic mind-brain science in a form that can be useful (applied) to problems of everyday life is a major challenge in many areas including education. Similar problems are faced in medicine. Jocelyn Kaiser in the 10 December issue of Science describes the creation of a new center at the National Institutes of Health devoted to translational medicine and drug development

14 Dec. 2010: Not a surprise but it is nevertheless an eye opener. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) compares the performance of 15-year-olds from 60 nations and half a dozen so-called regional economies on measures of practical knowledge in reading, mathematics, and science. Jeffrey Mervis reports all of the results in detail in the Journal Science (Dec. 10, 2010) but the punch line is that Shanghai China came in first place way ahead of the United States.

14 Dec. 2010: Carey K. Morewedge and colleagues published an article in the 10 Dec. 2010 issue of Science in which they report the results of several experiments in which they showed that just like having just eaten food imagining having eaten foods like cheese can habituate the eater so that he is less likely to seek more food. One practical implication is to have dieters imagine eating their favorite food and to do so often and vividly and in that way be less tempted to over eat especially fattening foods. One of the posted (fiction-imagination) stories on this website describes how imaging can also be used to help dieters lose weight.

17 Dec. 2010: How do memories form? This is one of the classic (basic) questions in mind-brain science. Proteins have been identified as one of the key players in establishing permanent memories. The work of Richard Huganir and colleagues have identified that one of these proteins calcium-permeable AMPARS that appear in the brain about two days after the experience of a traumatic event are essential for building brain circuitry that forms a memory.

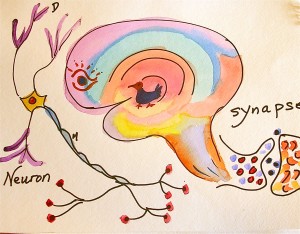

23 December 2010: Putting the pieces together will be the next great challenge around the mind-brain science corner. In the meantime we are making huge progress in picturing and understanding the elements of brain functioning. Seth Grant and colleagues at Cambridge (England) published their exciting findings in the last issue of Nature Neuroscience. They identified about 1400 different proteins involved in neural synaptic information processing. The 1400+ genes that specify these synaptic proteins represent 7% of the human genome. These are the proteins that are the basis of neural communication. Exciting stuff.

May-August 2010

2 June 2010 National Public Radio reported an update on the results of examining Albert Einstein’s brain. When he died neuroscientists, using the tools the then current aviable tools found that nothing really distinguished his brain from that of mere mortals. It wasn’ bigger, heavier, more convoluted. The story continues because we now know so much more about how to look at the brain and what to look for. It turns out that what was thought to be tissue that held the brain together (glia cells) were far more interesting and important to brain function. Read more about what we have learned about glia cells and Einstein’s brain in the short report below Can brain slices tell us about why someone like Einstein was so smart and creative? (see story below for more details).

13 June 2010: Nothing about mind-brain science is simple. Even when one can indentify some of the genetic variations associated with a disorder like autism the story that emerges is one that makes it appear that our task for understanding what is going on is in fact tougher, not easier. Louise Gallagher of Trinity College in Dublin and her colleagues just published a paper in June 9 in Nature on the genetic variations associated with autism. The study shows that the genetic variations found also vary across autistic individuals but the unique genetic variations seem to affect similar biological processes. A genetic ‘defect’ has long been seen as present in people with autism. What this study highlights is the need to understand more about how genetic factors work together, rather than separately to cause disease.