Towards a science of addiction: Issues, questions, future research directions

This report (story, posting, will include comments and responses from other scientists in the field of addiction)

Towards a science of addiction: Issues, questions, future research directions

I. Introduction

Defining an addiction

What does a Thesaurus search tell us about addiction? The terms that are highlighted first include: habit; compulsion; dependence; need; obsession; craving; infatuation; devotion. You get a similar profile of terms in German; Die Begriffe, die hervorgehoben werden zuerst sind: Gewohnheit, Zwang, Abhängigkeit, Not, Obsession, Gier, Verblendung, Hingabe.

Nothing much is either lost or gained in translation. In any language you get a superfical lay of the land of what it means to be addicted and barely touches the issue of the how and why of addiction.

overview

Brains are plastic. That is the brain is constantly being changed by experiences, learning, and all sorts of other events in our lives including the impact of drugs. Also, obviously, it is very well established that drugs of abuse are experienced as pleasurable and often exciting because of effects on the brain dopamine system. The brain never forgets. Unlearning, unlearning a pattern of abuse is incredibly hard. Think of drug addiction as a form of super learning. Bottom line, drug abuse changes the brain permanently.

What are the conceptual schemes used to think about addiction?

- It is a disease (like a fever without specifying the underlying cause)

- It is a brain disease (since whatever is wrong with you as someone addicted is happening in your head rather than in your big toe. It can be further specified in terms of brain areas that might be activated (or deactivated) in addiction along with neurochemical changes associated with addiction.

- It is a moral failing.

- It is a failure in willpower (which can be further specified as a failure in executive function skills).

- It is a learned habit, just like many others, but with the added feature of perhaps over-engaging the reward system of the brain.

- It is a a powerful (unforgetable) type of learning that also hyjacks brain control functions.

- A controls of the reward system are held captive by addicting drugs. The reward system in all of its neuroanatomical, neurochemical and genetic bits and pieces has been the focus of a good deal of addiction research. Terms like captured brains etc. are metaphors used to describe the state of addicted brains. It does appear that the addicted brain is running on automatic functions.

- I want to emphasize this last scheme for looking at addiction. It tends to be ignored and I think that is a strategic error. It seems equally important to concentrate on the double whammy of drug effects (and addiction) in the brain….that is deactivation of brain systems that are part of our executor, controlled (vs. automatic functions). So in a schematic I would picture what maintain and drives addiction is the synchronized dual action of activation (reward system and related circuitry) and suppression of frontal and prefrontal brain systems that are central players in controlling behavior.From this perspective an the mental functioning associated with addiction share much in common with disorders that are the expressions of anxiety and/or depression. For example, someone with an elevator phobia fully understands that their fear of elevators doesn’t make sense but other cognitive programs override the rational controlled logical cognitive function

- Our brain in love: Most of us have experienced being head over heals in love. Our brain in love is a high that totally controls and consumes all of our being, all of our brain. As someone addicted it would be virtually impossible to give up our lover, to disengage from a relationship that while very destructive is the most important attachment in our lives. Could you tell the difference between the addicted brain and the brain overwhelmed by the excitement and power of the lover in our lives?

- More about the brain in love: Breaking up is hard to do. The ending of a torrid love affair where the chemistry of attraction is overwhelming is a memorable painful experience. In fact brain-imaging studies has shown that many of the same brain regions active when experiencing physical pain are also the ones activated during the morning period of rejected love. I might suppose that the same love-related chemical attraction and then loss may be similar to withdrawal from our love object of desire, a drug that changes our inner being.

- Scales of value: Obviously the sauce of our addiction is more prized then so many other potential pleasures in our lives. One might conclude that in addiction what we value, including our interests are a very narrow spectrum of what we value.

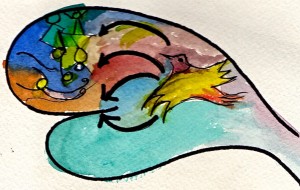

The three schematic sketches below illustrate brain functioning under ‘normal’ conditions, when driven (overwhelmed) by emotion-reward brain systems, and when executive functions suppress emotional responding.

I suppose I can add some additional ‘explanatory’ concepts to this list but won’t, at least for now. While all of these schemes provide us with description of what addiction is about, none provide us with what we need which is a perspective that can lead us to a discovering of the mechanisms of how addictions are established, the extent to which addictions are all the same (or different), the mechanisms that account for craving, mechanisms that might account for successful drug treatment, and the mechanisms that account for relapse,

Goals of addiction research are the obvious:

- Basic neuroscience related to addiction

- Prevention, risk

- Treatment, recovery, relapse

- Cultural, psychosocial factors

- Translational research (from basic to applied science)

- Goals would also be reflected in training

What reliable knowledge about addiction is currently available (both basic science and applied knowledge)

- What are the gaps in our knowledge

- Are we getting good value from our research investments

- How much of our current knowledge is not fit as a building platform for further productive research.

- How much of our research knowledge is solid trivia

Science is sold rather like any commodity. The climate of current research is focused on obtaining funding, advancing careers, and not necessarily solving problems. What is our current assessment of addiction R & D

Science relies on expertise and that expertise is often narrow in scope.

We train scientists to be successful in obtaining funds and not necessary to solve problems, take risks, be creative

II. What might be some features of an effective research culture

1. Different research milieus are appropriate for different research goals (small vs. large research settings, basic vs. applied research,….)

2. Are past successful R & D models like, NSF, NASA. Bell labs, useful in the design of future research environments and if so ….what features of those models are of value.

3. Can NIH extramural non-active researchers tell big time researchers what to do? Why would they listen? If the answer is that they won’t pay much attention to NIH ‘leaders’ then can you convince (win over) the research leaders to promote change in how research is funded and how research is managed.

4. Since much of current bio-medical research focuses on complex problems requiring interdisciplinary efforts how might NIH try and support more effective (integral) collaborations between individuals within a funded project and perhaps even more important between different research groups. There are three types of collaboration that come to mind.

Types of collaboration

- Small group collaborations: The most frequent collaborations are those that involve different experts coming together to work on a common project (lots of grants like that)

- Parallel like group collaborations: A similar but structurally different version of ‘a’ is when different groups of researchers work together on a complex project and each group works on a different facet of that problem. For example, take Alzheimer’s disease…. one research group might have key strengths in genetics and epidemiology, another in pharmacology, another in animal models, etc.

- Vertical collaborations: This is the type of collaboration that is implied when translational research is the goal. Can one develop effective, ongoing, research collaborations between groups of investigators that are working at very different levels of analysis….cell on up to normal and abnormal functions in humans?

- Collaborations are investigator driven and not mandated. What is expected is for collaborative plans to be made explicit in proposals.

- What are some of the inherent problems associated with collaborations of any sort? To address this question I reprint my note to Gina Kalata, NY Times article.

Dear Gina

Hope you had a pleasant, relaxing, fun thanksgiving.

Read your 26 Nov. NY Times cholesterol guidelines article. I know I repeat myself, but once again you do a superb job providing a clear picture of science findings, concepts points of view in areas (of medicine) that are complex and murky. Your (translation) articles are a huge plus for the general public.

Based on your article I am taking a crack at writing a posting on my website which I am revising once again after letting it rest in peace for the last half year while my grandson was slowly recovering from a bone marrow transplant. My grandson (11 year old Henry) and I worked on a child’s version of mindsinplay.com and I will post some of the material we put together on my old albatross site. Oh well, maybe this time the writing will catch up with the art.

Back to the point and what about your article has inspired me to write as a short piece about the frequently convoluted path of applying science to facets of life affecting many people. Your overview of the ‘bumps in the road….” could have been written about all sorts of biomedical clinical/applied research.

So what are the problems you highlight in your article?

Translation of the meaning and significance of new findings requires lots of work.

Old knowledge and ideas function as a firewall making it hard to accept new knowledge.

Understanding how to deal with complex phenomena is often based on incomplete use of what we know (and also biased choice of what data is and is not found useful).

So very often……The scope of the questions that can be asked (and answered) depends on the resources (money) available. Money also limits the extent to which existing knowledge can be adequately mined.

It is often difficult to get groups of experts (with different expertise) to work to work together to make effective science decisions (like policy recommendations in the case of cholesterol guidelines). Effective collaborations that work well often require a good deal of time to gel. Rapidly formed commissions or committees usually lack collaborative start up time.

Collaboration is often undermined by competition in the world of scientific research. The common goal (i.e., setting policy) is accomplished in a climate that is often not best suited to come up with the best agreed upon decisions.

Time constraints. So much of biomedical science (and science in general) is on a fast track. Empirical studies are published as fast as possible with little chance of replication. Obtaining funding is a number one priority in most science research, which requires working quickly and attractive packaging of research.

How people think and solve problems has been of interest to me for some time. I would bet that one could design an effective ‘environment’ for complex decision making such as is the case in establishing useful and reliable cholesterol guidelines.

All the best

Herb

III. Where questions being asked and research tools intersect.

- Driving research based on the relative power of research tools seems silly but asking questions that can’t be answered also makes little sense.

- A good deal of currently funded research yields solid findings but does not move us closer to answering

IV. Demonstration studies vs. mechanism oriented research

1. No doubt that demonstration type studies can be informative and open up new avenues of research. Systematically describing a phenomena is often the opening phase of a research program. This is perhaps especially true when the science demonstration does more than document the widely known and obvious results.

2. How do we scale comparative value and resource allocation for demonstration type research vs. studies that are designed to uncover underlying neurobiological mechanisms of a function under study?

3. A case in point: Would we have funded the ‘famous’ marshmallow study if it came up for review today. The answer is a qualified maybe and the maybe is based on a bit of luck and future prospects for learning more much more about impulse control. Back in 1970 Walter Mischel, a Stanford based psychologist did a laboratory study of 653 preschoolers who were given a chance to munch down 3 marshmallows immediately but alternative could choose to wait for some time and then get a whole load of marshmallows for their chewing enjoyment. No surprise, the vast majority of preschoolers chose to consume the 3 marshmallows in their hand rather than to wait for a whole lot more later. I suppose they must of have known about the saying ‘a bird in the hand is worth more than a bunch of birds in the bush. If that were all to the study many parents would have protested, money wasted, that Mischel needn’t have bothered. Mischel demonstrated the obvious.

That was the beginning of the study and not the end. For the next 40 years, count them, 40 years, Mischel followed his kiddies as they became adults. He found that the kids that had control of their impulses, that didn’t gobble up the marshmallows immediately, were far more successful in life than the kids who couldn’t stand the wait. It turns out that there SAT scores were on average 210 points higher, were far less likely to suffer from mental disorders, earned more money, were professionally more successful. In addition, brain imaging studies confirmed the differences, on average, of the brains of the kids who could control impulses as children from those who could not do so. The areas of the brain (frontal and prefrontal brain regions) that are well understood to be active in controlling impulses, in planning, were more active in the kids who could wait for the bigger marshmallow reward.

Impulse control is an important function for effective adaptive living. It is therefore no surprise that some educators have targeted this cognitive function for intensive training in young kids especially those who are poor and disadvantaged. Training of control functions is in fact at the core of a whole movement in education. One kind of charter school, the KIPP charter schools have demonstrated the value of training control functions, impulse control in disadvantaged children.

V. Filtering , transforming and using expertise (part of this is a continuation of issues raised under collaboration)

- Most neuroscience basic and applied research requires interdisciplinary efforts…..requiring input and output from experts that come from a variety of disciplines. How can we make better use of experts in solving all sorts of problems

- What experts have to offer in solving problems inevitably is filtered in the context of other’s expertise. The valuation, what is highlighted, dismissed, and altered in the translation of knowledge coming from one expertise domain into how others think about a problem determines how expertise is used.

- There is some value in serendipity when experts converge on a problem

- Are case studies of some value in defining how best to use experts in solving problems (i.e., a method used to advantage at the Kennedy School, Harvard, Public Policy). Examples of successes and failures

VI. Other strategies for consideration.

- Identifying talented scientists and providing them with support…via MacArthur model.

- Developing strategies for using experts and their input more effectively

- More effective vehicles for dissemination of research knowledge. Do current professional journals and science meetings adequately fit the bill for effective communication (small vs. large group meetings, format of articles in journals….)

- Wild card research initiatives. Can the professional outsider make effective contributions to addiction research? For example, mathematicians working on addiction models, biophysicists develop models of addiction recovery…..). Cross discipline contributions have been particularly useful in cancer research. How do you evaluate the potential value of disciplines that are, for example, at some distance from the life sciences?

VII. Making progress by asking good questions and organizing what we already know.

In an article published weeks ago in Neurophamacology (76, 235-249; 2014) Volkow and Baler grapple with the complex issues that are the portrait of addiction.

Their research journey starts with a combination of philosophy and cognitive science. The article begins with a quote from Victor Frankl’s, ‘Man’s search for meaning’ reflections on trying to keep a mind alive while facing death in a concentration camp. Volkow and Baler then explore and contrast the features of fast and slow cognition as described by Kahnemann and others. One type of cognition is deliberate, cool, strategic, involving awareness while fast cognition, as the name implies, is rapid, reflexive, ‘hot’ often emotional and uncontrolled. They then cite what is known about the underlying neurobiology of these two types of cognitive functions.

The point out what is well known, that drug abuse begins as voluntary behavior but then spirals into behavior that is uncontrolled automatic, compulsive and bypassing controlled cognition. In their opening remarks they also remark on the fact that drugs of abuse can incite epigenetic mechanisms that then affect gene expression which in turn can influence neuroplasticity.

That is where they start but then go on to consider the details of this picture of drug abuse. In the paper we can’t but note the impressive and extensive progress that has been made in the following areas of research.

Genetics

Heredity and drug abuse

Genes and their role in development

The genetics of personality as well as psychopathology which can the influence propensity for drug abuse

The role of genetics in the functioning of the reward system of the brain.

The genetic influence on brain plasticity.

Gene products that influence vulnerability to drug abuse.

Epigenetic

Environments alter the activity of brain circuits involving emotion, critical stages in development

The search for drug abuse related epigenetic alterations from amongst the huge number of such events that occur all the time.

Molecular level of analysis.

For example, drugs of abuse have a huge impact on the dopamine system of the brain (a neurochemical system that is a major player in the experience of reward)

Circuitry

We have learned a great deal about the neural circuitry that is important in slow, deliberate, top-down, cognitive functions, the kind that are at the heart of blocking impulsive behavior. This is also circuitry that is important in predicting reward, evaluation functions

Dysfunctional inhibitory control circuitry in addiction

Brain circuitry that is the foundation for accurately perceiving changes in internal states

The circuitry that is engaged in all sorts of conditioned learning

Circuitry that is the basis of motivation

Therapeutic interventions

i. All of the areas of research that are cited above provide potential targets for drugs that would treat drug addictions. For example, knowing what brain circuits are involved in drug abuse provide important clues for drug treatment development.

ii. Drug addiction can also be understood in terms of hot vs. cool cognition (or slow, deliberate controlled cognition vs. reflexive, automatic. Impulsive, fast cognitive responding). Why not capitalize on that idea in the area of both prevention and treatment.

Slow controlled is also is what is often labeled executive cognitive functions. These functions, cognitive skills can be and are learned (just like all sort of skills). One of the major outcomes of normal development involves learning those skill (i.e., from parents). A considerable body of research points to the value of teaching executive function skill through games to disadvantaged preschoolers (see the work of Adle Diamond). Therefore …..

a. Why not use executive function training (especially in at risk kids) as an intervention that has drug abuse prevention properties.

b. Could executive training be a perhaps be used as an additional drug abuse treatment?

Sketchbook of facets of addiction

If it feels good, and it looks good, then why not

Multiple paths to nowhere but maybe this time…..

So many possible mechanisms

Multiple faces and features of addiction

Seduction has been around forever

Beneath the surface there is turmoil